A Framework for Testing and Experimentation

Building Speed, Efficiency, and Confidence Without Breaking Trust

Most organizations believe they have an experimentation culture. In practice, many are still operating under rules that made sense a decade ago but quietly collapse under modern conditions.

The classic model is familiar. Run an A/B test. Wait for statistical significance. Declare a winner. Move on. That approach assumed clean user-level tracking, stable channels, and patient stakeholders. None of those assumptions reliably hold anymore. Channels fragment. Privacy constraints erode signal fidelity. Product, marketing, and data systems are tightly coupled in ways they were not before.

The result is predictable. Experimentation either slows to a crawl because no one trusts the data, or it speeds up in the wrong direction, with teams over-interpreting weak signals and shipping changes that do not reproduce. Both outcomes undermine confidence. Over time, experimentation stops being a decision engine and turns into performance theater.

The framework I’ve outlined here exists to break that cycle. It comes from building growth and experimentation capabilities inside real organizations, not idealized ones. Again and again, the issue was not ambition or tooling. It was the inability to align process, analytics, and decision-making with how experimentation actually functions inside companies.

At the core is a simple but often ignored truth: not all tests deserve the same process, the same resourcing, or the same definition of confidence. Treating them as interchangeable is one of the primary reasons experimentation programs stall.

Why legacy experimentation models fail in practice

Most experimentation failures are not caused by a lack of ideas. They are caused by habits formed in a simpler measurement era. Teams still operate under implicit assumptions about clean attribution, stable platform behavior, and linear decision-making. Worse, there is often a belief that enough calibration or methodological rigor will eventually “clean” fundamentally noisy data.

In practice, experiments are routinely compromised before they finish, often by well-intentioned behavior. Teams peek early. Metrics shift mid-test. Timelines are extended or shortened until something looks acceptable. Each action feels reasonable in isolation. Collectively, they inflate false positives and create a backlog of changes that feel successful but do not hold up over time.

Leadership notices. Not because leaders are statisticians, but because outcomes stop compounding. Trust erodes even when results appear directionally correct.

At the same time, modern data stacks introduce failure modes older playbooks never anticipated. Sample ratio mismatch, identity loss across devices, platform-side filtering, and logging gaps quietly distort outcomes. When data integrity is not treated as a prerequisite, organizations end up debating conclusions that were never reliable to begin with.

The final failure is organizational rather than technical. Teams run isolated tests without shared hypotheses, comparable metrics, or agreed confidence thresholds. Learning does not compound. Experimentation becomes a series of anecdotes instead of a system that builds institutional knowledge.

This framework addresses these failures by forcing clarity upfront. What kind of test is this? What rigor does it deserve? And how should results be interpreted before anyone sees a chart?

The part most frameworks avoid: experimentation is political

There is another reason experimentation breaks down that most frameworks avoid acknowledging. Belief inside organizations is not purely rational. It is political.

Experiments do not exist in a vacuum. They exist inside power structures, incentive systems, career risk, and narrative momentum. Data does not simply inform decisions. It is used to justify them.

This is why some experiments are allowed to “fail fast” while others are endlessly scrutinized. Results that align with existing strategy are accepted on weaker evidence. Results that challenge it face higher confidence bars, deeper analysis, and longer delays. The same organization applies different standards without ever stating them explicitly.

Ignoring this reality does not make experimentation more objective. It makes it more fragile.

The goal of a modern framework is not to eliminate politics. It is to constrain its influence by setting expectations before results exist.

The four-quadrant model for modern experimentation

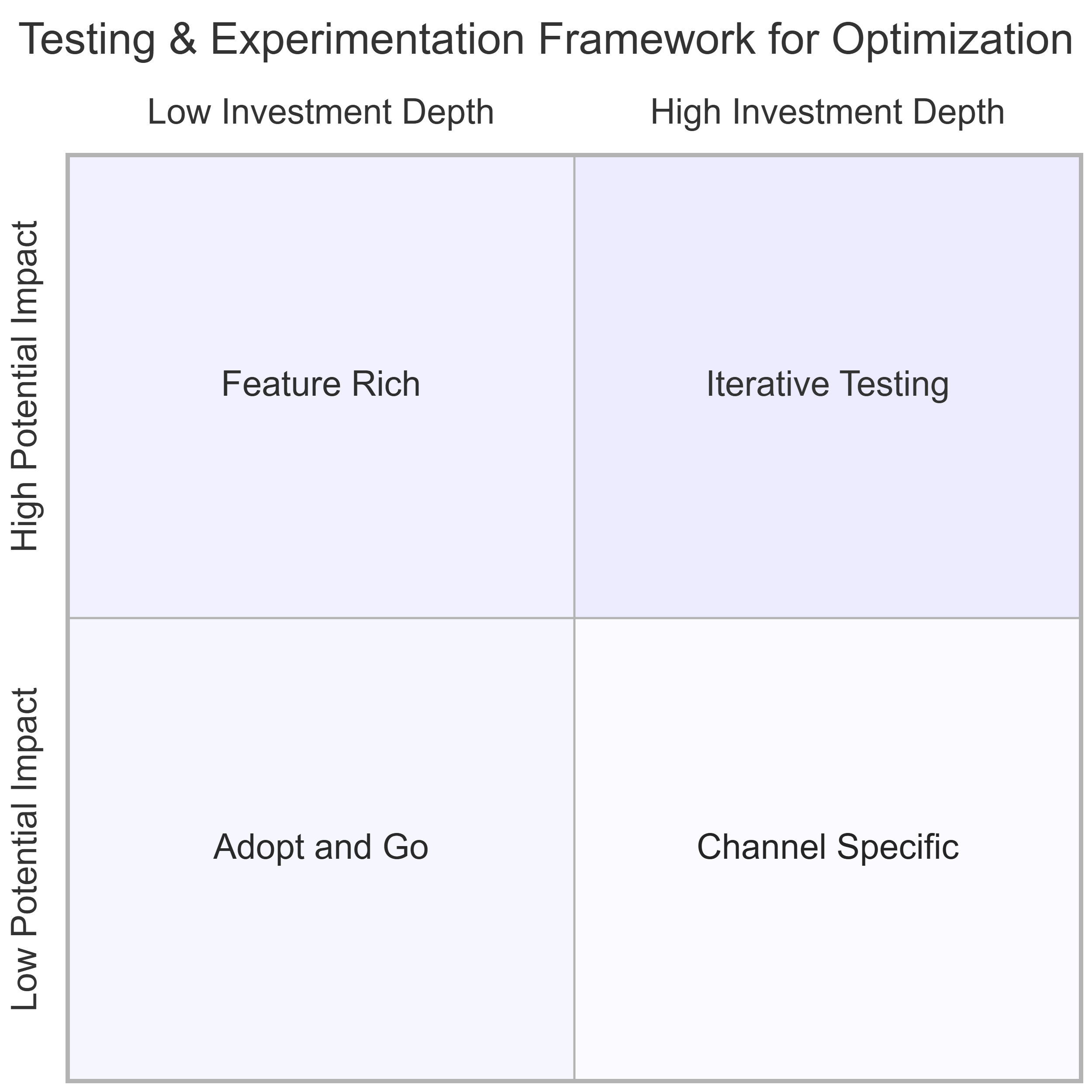

The framework organizes experimentation into four quadrants based on potential impact and investment depth. The purpose is not categorization for its own sake. It is alignment. Different kinds of work require different rules of engagement.

Feature Rich experiments sit at the high-impact, high-investment end of the spectrum. These are not incremental optimizations. They are ambitious initiatives designed to change how the business works. Product experience, pricing, onboarding, messaging, and operations often move together under a single hypothesis. These experiments are meant to swing for the fences.

Because of that ambition, Feature Rich work requires coordinated investment across product, engineering, design, data, marketing, and leadership. These are strategic bets, not routine tests. They demand upfront alignment on scope, success criteria, and failure thresholds, along with explicit agreement on how long the organization is willing to learn before deciding. Their value is not just in winning, but in shaping future roadmaps and experimentation priorities.

Iterative Testing plays a different role. This quadrant exists to isolate and refine variables surfaced by Feature Rich initiatives or introduced as net-new ideas that do not require full organizational mobilization. These tests are designed to answer precise questions quickly and clearly.

Iterative Testing is intentionally lighter-weight. The goal is learning efficiency. Teams should be able to run these tests frequently, stack incremental improvements, and build confidence in causal relationships without long planning cycles or executive gating. This is where experimentation earns velocity and credibility.

Channel Specific testing is narrower by design. These experiments focus on optimizing behavior within a single environment such as paid search, social platforms, CRM, SEO, or affiliates. Their value comes from control and clarity, not breadth.

Channel tests require fewer dependencies and should move quickly. Treating them as if they deserve the same governance as major product changes creates friction without increasing insight. This is where many organizations slow themselves down unnecessarily.

Adopt and Go completes the framework. This quadrant exists to prevent wasted effort by leveraging ideas that have already worked in lookalike contexts. Another brand. Another market. Another segment. The goal is not invention, but translation.

Adopt and Go relies on staged validation rather than blind replication. Even proven ideas can fail when context shifts. The discipline is knowing when enough confidence exists to scale and when adaptation is required. Organizations that lack this muscle either over-test obvious wins or roll them out recklessly.

Deterministic and probabilistic analytics as an operating reality

A critical insight behind this framework is that analytics is not monolithic. Speed, efficiency, and confidence depend on using deterministic and probabilistic methods intentionally, not interchangeably.

Deterministic analytics relies on explicit linkage through known identifiers such as authenticated users, order IDs, or server-side event joins. It is essential for validating instrumentation, diagnosing funnel mechanics, and establishing causal relationships when identity coverage is strong. Deterministic measurement provides operational truth.

Probabilistic analytics exists because deterministic coverage is often incomplete or intentionally constrained. Privacy limits, cross-device behavior, and platform opacity make inference unavoidable at scale. Probabilistic methods estimate impact when user-level paths are fragmented.

The failure mode is arguing which method is “right” after results appear. The correct method is the one agreed upon before the test launches, based on the quadrant and the decision at hand.

Feature Rich experiments require deterministic validation of implementation and downstream behavior, but often need probabilistic or incrementality-minded approaches to assess whether observed lift is truly net new once the system adapts.

Iterative Testing should rely primarily on deterministic analytics. This quadrant exists for causal clarity. If integrity cannot be established here, the test should not ship.

Channel Specific testing often lives at the boundary. Deterministic measurement works when first-party signals are strong. When they are not, probabilistic interpretation is the reality. Confidence comes from repetition and triangulation, not a single dashboard.

Adopt and Go uses deterministic analytics to confirm correct implementation and comparable behavior, while probabilistic methods help assess whether expected performance transfers across contexts. The goal is risk reduction, not novelty detection.

Confidence, governance, and decision-making

The most important principle across all four quadrants is that confidence should scale with consequence. High-impact, high-investment decisions deserve deeper validation and slower calls. Low-impact, low-investment decisions deserve speed and autonomy.

When organizations invert this logic, experimentation becomes either painfully slow or dangerously noisy. This framework gives leaders a shared language to avoid both extremes. It does not promise certainty. It promises alignment.

The goal is not more experiments. It is better decisions made at the right speed, with confidence levels that match the stakes. That is how experimentation becomes a durable advantage rather than a recurring source of friction.